Lady Shirley is back again and getting political! Wait…not THAT kind of political. She has some “Presidential Ponderings” on her mind and is ready to Spill the Tea! We’ve had some interesting Presidential connections to Concordia she’d like to share. Let’s see what she has on her mind…

EMBEZZLEMENT

Before this author begins her “Presidential Ponderings,” new developments have come to light regarding the “Women of Cloud County” Edition back in May, Miss Minnie May McKay was featured as the first woman to hold the office of Cloud County Treasurer.

This author stumbled upon an article penned by Clarence Paulsen about Miss McKay from January of 1983. Unable to turn away from scandalous tales, this new information may bring questions regarding Miss McKay’s tenure.

October 2, 1933, Minnie May McKay was placed on trial for embezzlement and forgery charges. More than three years after Miss McKay vacated her position as County Treasurer, $8,365.81 had been found missing from the treasurer’s books, but less than three years since the auditors found the discrepancy Minnie May was charged. As it would turn out, the three-year statute of limitations on had expired. Mr. Paulsen states, “The prosecution could and did prove that the money disappeared while Miss McKay was the county treasurer. It could not prove to the satisfaction of three of the jurors that she had appropriated the missing money to her own use She had not engaged in high living, nor was there any evidence that she had gambled or given the money away. There was gossip on the street about John Mallory, a barber, with whom she had long kept company, but there was not a shred of admissible evidence that he got any of the money. … The judge declared a mistrial and discharged the jury which was hung nine for conviction and three for acquittal.”

Miss McKay left Kansas to live with her brother in Chicago and after his death moved to California. What came of the $8365.81, a rather large sum for the time, shall ever be left to speculation.

MRS. WASHINGTON

One of seven currently known letters between Martha Washington, wife of President George Washington, and her favorite niece Frances (Fanny) Bassett Washington, wife of Major George Augustine Washington, George’s nephew, was found in a file cabinet in 2011 at the Cloud County Museum.

The letter was donated to the Museum after the death of Mrs. Park Pulsifer in 1948. It had been in her possession and authenticated in 1920. In an interview of the Museum’s co-curator of 2011, it was stated that the letter was tucked in a file folder that had fallen to the bottom of the file cabinet only to be discovered when the cabinet was moved.

At this rediscovery, the Cloud County Historical Society held an unveiling of the letter. Over 200 visitors, including descendants of George and Martha Washington were in attendance.

Martha wrote Fanny from the Presidential residence in Philadelphia on January 27, 1793. Fanny was living at Mount Vernon caring for the home while the Washingtons were in Philadelphia. In the letter, Martha expresses deep concern for Major George Augustine’s declining health. She shares her deep longing to return to Mount Vernon though she knows they cannot return until Congress adjourned in March. She also comments that the roads would be too poor to travel until then as well.

This letter has found historical significance in that it reflects Martha’s maternal instincts, a sense of duty to her station as First Lady, and her emotional sadness for the declining constitution of Fanny’s husband during a difficult time. The letter’s warmth toward her niece gives the nation a glimpse into the heart of our first First Lady. Sadly, Major George Augustine Washington passed away 9 days after the penning of this letter.

The remainder of the letters between the two are currently scattered among museums and collections across the country.

A VICE-PRESIDENTIAL DETOUR

Friday the 6th of August, 1915, a freight train stopped in Concordia. Generally a common occurrence in 1915, as trains passed through often, this train coming from Lincoln, Nebraska held an unexpected passenger. Vice-President Thomas Riley Marshall. Woodrow Wilson’s VP was heading to Beloit, Kansas. He missed his connection in Lincoln. To make his scheduled appearance as the featured speaker at Beloit’s Chataqua, the next in succession to the presidency of the United States had to hop on a train heading through Concordia.

Accompanied only by his secretary, our favorite author Clarence Paulsen writes, “riding unobtrusively in the cupola of a caboose at the tail end of a west- bound Missouri Pacific “Red Ball” freight train. … A Daily Blade reporter surprised him in his shirt-sleeves in the cupola of the caboose and got an interview.” This author, at time of this penning, is still searching for that interview transcript in the archives of the Daily Blade.

BOSTON CORBETT

An evening at the theatre ended in tragedy April 14, 1865. President Lincoln was seated in a box seat, not unlike the box seats at the Brown Grand Theatre, when a man named John Wilkes Booth entered his box, pointed his pistol, and shot President Lincoln in the back of the head. He reportedly jumped out of the box, onto the stage, where he broke his leg, and escaped from the theatre. Twelve days later, on a farm in northern Virgina, Booth was tracked and found in a barn where Union soldier, Boston Corbett, fatally shot him.

It has been 160 years since Boston Corbett shot John Wilkes Booth, but his legacy in Concordia lives on.

Thomas H. “Boston” Corbett was born in London, England in 1832. He immigrated with his parents to New York when he was around 8 years old. He learned the milliner trade, hat making, from his father, holding that occupation intermittently from his teen years throughout his life. In 1850 he married a woman, Sarah, 13 years older, became an official American citizen in 1855, and moved to Virginia.

Corbett had a difficult time in the Antebellum South as he was vehemently opposed to slavery. A year later the couple decided to return to New York by ship, but sadly Sarah died before arriving. Following her burial in New York, he moved to Boston. This is where his life begins to twist toward the bizarre.

Unable to keep a job due to his grief and heavy drinking, he becomes homeless. After a night of excessive drink, he is taken in by a street preacher and persuaded to join the Methodist Episcopal Church. Strongly against alcohol, they sober him up, he swears off alcohol, and undergoes a religious epiphany.

He returned to hat making and was often found preaching while at work and as a street preacher earning his reputation as an eccentric and religious fanatic. His mind troubled with impure thoughts and still grieving his wife, he reads a bible passage that convinces him to castrate himself. He is baptized a few days later and begins wearing his hair long to imitate Jesus. As Boston is the place of his conversion, this is when he takes the name for himself. Scott Martelle’s book, The Madman and the Assassin, may be the most comprehensive scholarly source for understanding Corbett. In that book, Martelle describes Corbett’s personality. “Corbett was described by those who knew him as friendly and open, helpful to those he saw in need, but also quick to condemn those he thought were out of step with God.”

In 1861, during the Civil War, Corbett enlisted in the military with the anti-slavery Union Army in New York (where he was required to cut his hair). He was described as a good soldier, but with a propensity to preach, carrying his Bible with him wherever he would go. He was known to scold fellow soldiers and even superiors when they used profanity or engaged in other sinful behaviors. Often this led to physical altercations. One such altercation found him court martialed, facing a firing squad, but instead discharged from the army. Unsatisfied, he re-enlisted in another regiment.

By 1864, Corbett found himself in a battle in Andersonville, GA, which ended in a shootout and his capture and imprisonment, with thousands of other soldiers, in a Confederate prisoner of war camp. Five months later, he was released and promoted. Five months following his release, President Abraham Lincoln is assassinated.

Corbett was part of the military regiment leading the hearse. He was one of the first to volunteer to join 26 soldiers that would follow a lead to capture John Wilkes Booth and his accomplices and was allowed to lead a prayer over President Lincoln’s death at a chapel service that evening.

The soldiers traveled to Virginia and surround the farm and barn where they were hiding. Booth’s accomplice surrendered but Booth declared he would not be taken alive. They set the barn on fire to lure him out, but he wouldn’t leave. Corbett volunteered to go inside and subdue him, but the offer was declined. After a time, he spied Booth through a crack in the barn. He took aim, no intent to kill, when Booth moved. The bullet entered in the base of his head and exited the neck, coincidently, in nearly the same spot Booth shot Lincoln. Paralyzed and in excruciating pain, he died 2-3 hours later. Days of interviews determined Corbett did his duty well, as his orders were to capture Booth. They didn’t specify alive or dead. He was praised as a hero by the public and the press.

After the war, southern sympathizers began sending him death threats. He was convinced that Washington high administration was angry with him for killing Booth. In fear they were searching for him, he began carrying a pistol to defend himself.

His mind troubled recalling Booth’s death, difficulty keeping a hatting job, and his propensity for preaching, eventually led him to Concordia in 1878. He acquired a plot of land and built a dugout home. He mostly kept to himself in the 8 years he lived in here. Years of exposure to mercury (II) nitrate in hat-making, likely caused the anxiety and paranoia that Booth’s family and the U.S. government were looking for him. He didn’t like to talk about Booth and instead utilized his sermons to avoid it. As he became more paranoid, he stopped coming into town completely. He would ask a “trusted” neighbor to bring him items he needed from town, but they had to leave them a mile away from his home for fear of being found.

In 1887 he secured a job at the House of Representatives. An incident at the House ended with him placed in an asylum. He escaped in 1888 to Neodesha, Ks and told a friend he was headed to Mexico, never to be heard from again.

Information gathered is intended to be factual and entertaining compiled from multiple print sources and interviews of those who remember our histories. For more information on resources, please contact Cloud County Tourism.

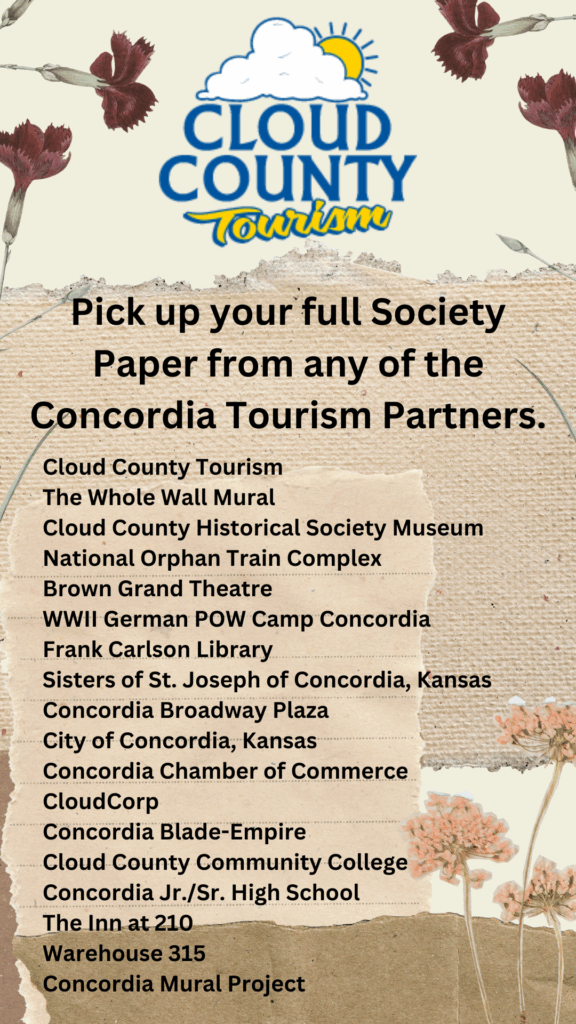

Download your printable copy here. (Be sure to fold the paper in half lengthwise for ease of readability.)